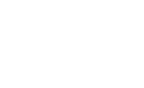

Herbert Howells and Hymnus Paradisi

Written by Simon Heffer, Chairman of The London Chorus

Hymnus Paradisi, which The London Chorus will be performing on 7th March, is a work that many regard as Herbert Howells’s masterpiece. It was written in 1938 but not performed until 1950.

Howells’s first musical experience was in the Anglican church, as a choirboy, and later standing in for his father to play the organ. His first serious musical education was in the great cathedral at Gloucester and then at the Royal College of Music. He wrote much of his music in a choral tradition that, not least because of its umbilical association with the Church of England, is considered peculiarly English. He loved the landscape of his native Gloucestershire and immersed himself in English literature.

When I listen to most of Howells’s music I find myself observing that it could only have been written by an English composer: and, more particularly, by an English composer writing in England in the early and middle decades of the last century. Why is this? Because in its idiom so much of Howells’s music is reminiscent to an extent of that of the choral tradition developed by his teacher Sir Hubert Parry, and to a much greater extent that of the general idiom of his friend and inspiration Ralph Vaughan Williams. The former, as some of you may know, told the latter, when VW was Parry’s pupil at the Royal College of Music, that he should go out and write choral music “like an Englishman and a democrat”. In his own choral works of the 1880s and 90s, and despite his often-acknowledged debt to Brahms, Parry had discovered something far more democratic than many of the composers who influenced him – music straightforward for English choirs to sing, and composed in an idiom whose simple nobility reflects that of the often biblical texts that he set. I hear this in so much of Howells’s church music and, albeit in a highly stylised and developed form, in his Hymnus Paradisi.

Thus Parry himself became an English composer by style as well as by birth, not least because for all his Germanism he set some of the rules of a whole new school of English composition and helped settle what that style should be: and Vaughan Williams, with his determination to use modal music and English folk-song to influence his own composition in order to make it truly “national”, set most of the rest. The effect of modal counterpoint, which originated in Europe in the 12th or 13th centuries and was the foundation of much English music in the 15th and 16th centuries, runs through most of Howells’s music.

Vaughan Williams had his definitive effect on Howells when the latter, as a boy of 18, heard the first performance of the Fantasia on a theme by Thomas Tallis at the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester in September 1910. As he wrote subsequently: “I didn’t understand it, but I was moved deeply. I think if I had to isolate from the rest any one impression of a purely musical sort that mattered most to me in the whole of my life as a musician, it would be the hearing of that work.” The Tallis Fantasia was one of the first products of VW’s conscious desire to develop an English style of composition based on historic forms of English music. The effect it had on Howells fundamentally co-opted him into the school that VW, with help from Holst and the approval of Parry, was establishing.

Howells was just 23 when he was diagnosed with the life-threatening condition of Grave’s disease: but his life was saved, effectively, by Sir Hubert Parry, who paid for him to be one of the first men in Britain to undergo radium treatment, invented just a few years earlier by Pierre and Marie Curie. That Howells lived into his 91st year shows just how successful the treatment was. His sickness made him medically unfit to fight in the Great War, which may also, ironically, have saved his life.

Yet for much of his life Howells was not, so far as the public was concerned, really a composer at all: he was a teacher, adjudicator and examiner. The first performance of second piano concerto in 1925 – a work in a very different idiom from its withdrawn predecessor – was sharply heckled, and this caused him to slow down his rate of composition and to stop seeking publication or performances of such new works as he did write. His cello concerto, now happily completed and realised on disc, remained unfinished because of his nine-year old son Michael’s sudden death from polio in 1935, while the family were on holiday in Gloucestershire. That intensely traumatic event temporarily silenced Howells as a composer, until his daughter, who grew up to become the famous actress Ursula Howells, prompted him to write Hymnus Paradisi: but even that, for reasons connected, perhaps, as much with a lack of confidence as with the intensely private nature of the grief that had triggered the work, took a dozen years to see the light of day, and only then at the urging of Herbert Sumsion and Vaughan Williams.

Howells wrote Hymnus Paradisi before he made his reputation as the premier writer of church music in England in the 20th century. Yet because of the long interval between its composition in 1938 and its first performance in 1950 by the time it appeared his reputation in that field was already well established, following some highly productive years in the 1940s, including Howells’s time as director of music at St John’s College Cambridge. Hymnus Paradisi was composed too with an implicit understanding of the space in which it is designed to be performed. Howells had a lifelong love of church architecture and of medieval cathedrals especially. It is their ambience that his church music fits like the proverbial glove. Howells to an extent re-made the tradition of English church music in the 20th century: his masterpiece, which he defiantly but I think accurately said was not “churchy”, sits firmly in that tradition.

The first time I ever heard the work – I had never even heard a recording of it at the time – was in the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge, when I was an undergraduate. I was at the concert partly by accident, for it was May Week and there were rather a lot of other things to do. I doubt I was the only member of the audience to be stunned by a magnificent performance of it, and to have had a moment of revelation similar to the one Howells himself had in Gloucester Cathedral in 1910 when he first heard the Tallis Fantasia. Among my many memories of that evening was the perfect way in which the great perpendicular building complemented the music: how, it being the middle of June, light poured in through the great East window right through the performance; light is the quality that Howells strives to find in the work, to alleviate the darkness of his shocking bereavement. But I also remember most of all how an old man in a dark suit was hauled up out of the stalls to wave his walking-stick at an audience whose already huge applause multiplied when it was realised the old man was the composer himself, four months before his 90 th birthday and eight before his death. It was an awesome moment.

Frank Howes, The Times’s music critic, reviewing the first performance at the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival in 1950, felt he indeed identified the theme of ‘light’ pervading the work, influenced by the powerful stressing of the phrase lux aeterna in a charismatic passage in the Requiem Aeternam. Yet the tone of work is set by the arresting, and unequivocally dark, four-bar theme that opens it, played on violas, clarinets and bassoons: a theme that returns at the very end. This is not the conventional Christian understanding of redemption and life everlasting, but a temporary consolation to the bereaved, and an altogether more philosophical, and bleak, meditation on the true meaning of death in the estimation of an agnostic or atheist in the English secularist tradition. That would seem to be settled not merely by the majestic sadness of the opening and closing theme and the unity it imposes on the work, but also in the grandeur of the emotion in the opening passage of the finale, Holy is the true light, and in occasional moments of almost theatrical distress that occur in the work, and which go beyond straightforward grief: such as at point 3 in the recently-revised score, or in the daunting crescendo just before point 15. Coming in what, in its idiom, is a deeply English work (and could be no other) these exotic moments of soul-bearing stand out, and remind us of the composer’s hopelessness in his loss. In Vaughan Williams’s letter of condolence to Howells on Michael’s death, VW observed: ‘One feels the futility of all the things one usually sets value on when one is faced with reality’. Hearing this monumental work, which we really should do more often, one is struck by how very much Howells seems to have taken this to heart.

Light – lux perpetua – was for that reason what the composer sought in writing the piece. It is just visible, but there is darkness nearly everywhere. The power of the work is apparent in its opening few bars, which are so laden with sorrow that one wonders how it is going to find the will to go on. Before long sorrow turns to anguish; and the opening motif of loss and suffering recurs later on, whenever it seems the sun might just be breaking through. Yet this is a mournful work only in parts; there is none of the self-pity that we associate with the expression of grief in other societies; it is borne with fortitude in a very English way, which is, apart from its beautiful sonorities, so much of the work’s appeal.

Perhaps the ultimate irony of this most religiose of works from a man who started out as a cathedral organist and made his name writing church music is that Howells’s own relationship with religion seems to have been far from clear. The abyss into which he sank after Michael’s death suggests the consolations of the church were inadequate. Howells certainly had a private life not easily compatible with godliness: he was a habitual womaniser. Hymnus Paradisi is a setting of words from the Latin mass, the Psalms and other religious texts, and relies on some of the classic tropes of devotional music – notably the organ – for its profound effects. Yet it comes over as a rather secular work, dealing more with the realities of a shattering bereavement than with any spiritual exploration that that event might provoke.

It is, too, a work of astonishing feeling, as its motivation might suggest: but it is here that matters become more complicated. Some of the material is a re-working of parts of a Requiem for unaccompanied voices that Howells had written in for King’s College, Cambridge in 1932. Yet, as Paul Spicer tells us in his thoughtful biography of the composer, Howells was not a particularly religious man; indeed, by the end of his long life he seems not to have been religious at all. Hymnus Paradisi appears to comply with what by 1950 had become the Vaughan Williams tradition of writing religiose music, namely that the composer did so with a sense of detachment from any religious sensibility.

It is, instead, specific to Howells’s grief, which Spicer also details in his book. It seems to have been some years after the boy’s death that Howells and his family scaled down their frequent pilgrimages to his grave in a Gloucestershire churchyard. In the months immediately after the tragedy they were there weekly, if not daily. It is instructive to hear the beautiful settings of the Requiem Aeternam in the original Requiem, and then to compare them with the second section of Hymnus Paradisi. It is the difference between detachment and involvement; between a piece of music written for use after the death of a fellow human being with whom one was not necessarily connected, and for the death of one’s own flesh and blood.

More than 40 years after Howells’s death his reputation as the great composer of English church music in the last century remains unchallenged. I very much agree with Howells that Hymnus Paradisi is not ‘churchy’, but produced by a man with a tremendous facility for writing church music, and with a profound talent for doing so. As a composer, he displays a typically English touch of blending an idea of the godly with the secular – in this case only three of the six movements set any words from the liturgy. In doing so, in his efforts to express the crushing personal grief that he felt, he created one of the great works of the whole musical canon, and one that stakes a claim to be the finest piece ever written in the English choral tradition.